Introduction

This post is about tribalism in contemporary Western culture, and specifically it’s about the invisible assortment of people who have self-selected out of it.

Maybe the most interesting thing about this post is that it’ll seem weird and esoteric to most of the people I know in real life but completely mundane and obvious to most of the people I know on the Internet.

The two tribes

In the United States (and to some degree the whole Western world) there are two super-groups that define the cultural landscape: the Red tribe and the Blue tribe.

Psychiatrist blogger Scott Alexander once illustrated the cultural markers of the Red and Blue tribes:

The Red Tribe is most classically typified by conservative political beliefs, strong evangelical religious beliefs, creationism, opposing gay marriage, owning guns, eating steak, drinking Coca-Cola, driving SUVs, watching lots of TV, enjoying American football, getting conspicuously upset about terrorists and commies, marrying early, divorcing early, shouting “USA IS NUMBER ONE!!!”, and listening to country music.

The Blue Tribe is most classically typified by liberal political beliefs, vague agnosticism, supporting gay rights, thinking guns are barbaric, eating arugula, drinking fancy bottled water, driving Priuses, reading lots of books, being highly educated, mocking American football, feeling vaguely like they should like soccer but never really being able to get into it, getting conspicuously upset about sexists and bigots, marrying later, constantly pointing out how much more civilized European countries are than America, and listening to “everything except country”.

It’s not about politics

“So it’s Republicans and Democrats, right?”

The two tribes are cultural, not just political. The only reason we notice the political differences is because that’s the arena where the two tribes openly contest with each other—the president will be either Red or Blue, congress will be majority Red or Blue, etc. In all other domains, the tribes are mostly content to ignore each other or non-confrontationally gripe about each other.

Scott’s descriptions were written 10 years ago, but they hold up quite well. Ironically, the thing that has changed the most over time is the political positions of each tribe. In 2014 you would’ve said Blue is fiercely skeptical of the pharmaceutical industry and would never trust Pfizer to deliver a world-saving drug in an emergency. You would’ve said Red is more keen to censor public speech that violates their taboos. You would’ve said Blue, being strongly in favor of bodily autonomy, would never want to force a healthcare procedure on anyone. You would’ve said Red is conservative and scrupulous and would never elect a twice-divorced foul-mouthed billionaire playboy as their presidential candidate.

That’s because politics is downstream of culture. Most often, a person’s tribal affiliation establishes and reinforces their political opinions, not the other way around. Tribalism is not fundamentally about political ideas (or ideas, at all).

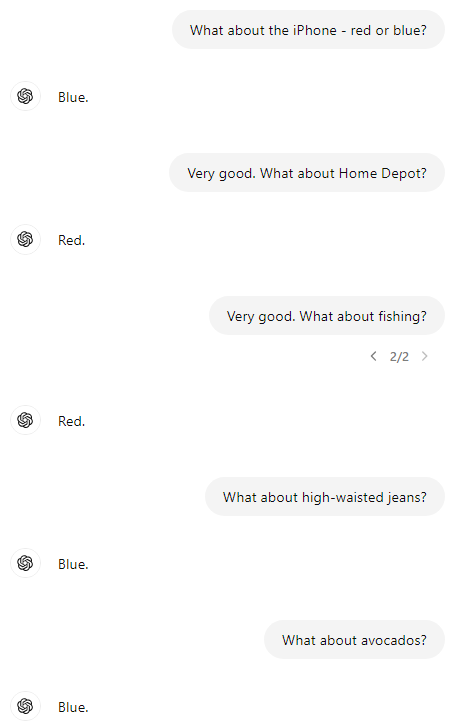

Once you see the two-tribe dynamic as cultural, not just political, you see it in everything, not just politics. The classification is so easy, ChatGPT can do it flawlessly with very simple prompting (I didn’t even tell ChatGPT what the Red and Blue tribes were. I asked it to give me its own definitions at the beginning of our conversation):

Is there anything about wearing high-waisted jeans that inherently makes you want to go out and march for George Floyd? Or vice versa? No—yet you know there’s a correlation. The only connection they have is that they both belong to this giant cluster of memes called “the Blue tribe.”

It’s not about anything

“If the essence of each tribe is not its politics, then what is it?”

Some psychology researchers have posited that it’s all about psychological profiles: Blue have high openness to experience, Red have low; or Blue have high empathy, Red have low. Others say it’s about values: Blue’s ultimate value is equality; Red’s is… perhaps tradition, though there’s variance in which traditions are considered the good ones.

But maybe all of this is misguided: why does a tribe need to have an “essence?” You’ve lived your adult life embedded in a group of people; almost all of them hold certain values in common; do certain behaviors in common; have certain aesthetic preferences in common. And when you fit in with them, they treat you well. We have much more evidence of people making personal choices based on social consensus than of people choosing their social group based on predetermined personal values or psychological traits.

Coordination

“If the characteristics of these tribes are arbitrary, then why did they form that way? Why not form around a real dichotomy, like blue-collar vs. white-collar, or introverts vs. extroverts?”

Sure, there are infinite ways we could group people, but not all groups are tribes. What marks a tribe is its ability to coordinate—to make the behavior of each member predictable to other members, so they can take personal risks to cooperate together and not worry about being betrayed. It’s about winning the Stag hunt game, in a thousand little ways every day.

According to signaling theory, coordination points should be arbitrary. If the founding principle of the group is “introverts / extroverts,” then the loyalty of its members isn’t clear. Are you a member because you unconditionally care about the tribe? Or are you just here because you’re in-fact an introvert? If it’s the latter, then why should I trust you over a random stranger?

Of course, eating avocados or having the latest iPhone aren’t good signals either—tons of people just like avocados and iPhones. But when you follow a hundred more of those Blue-tribe traits, and they have no logical link to each other, then the pattern becomes unmistakable: you belong to the tribe.

Disillusionment?

“It seems silly to choose your values and behaviors and preferences just because they’re arbitrarily connected to your social group.”

If you think this way, then you’re already on the outside. You’ve escaped orbit; you’re a free body now. If you’re thinking, “Wait no, I’m pretty sure my group is fundamentally about X, which is fundamentally good,” then you’re probably still in Red or Blue. And God bless ya, I’m not intent on shaking you out of orbit. But anyway, read on to learn about the people who have been shaken out. Where did they end up?

Look closely, because they’re invisible to you. To a Red or Blue member, anyone who’s not a fellow member must have gone to the “other” side. That’s not true though; there’s much going on outside of the Red-Blue paradigm. I’ve spent a lot of time in some of these quiet cultures, and I want to tell you about them.

The third “tribe”

Scott Alexander called it the Grey tribe. Statistician / forecaster Nate Silver called it the River. Cognitive scientist / entrepreneur Tyler Alterman called it the metatribe. They’re all pointing at basically the same thing. It’s a third distinct cluster of cultural fragments that collectively forms a subculture in the West.

It’s characterized, most of the time, by: libertarian political views (often emphasizing freedom of speech); affinity for (and often optimism about) technology; humanist philosophy; belief in the importance of modeling the physical world and in the value of the scientific method as a means to that end; a desire to analyze everything and extract general rules, and a tendency toward high-decoupling (e.g. separating truth from aesthetics; morality from emotions; generally, disconnecting ideas from each other). In aesthetic preferences there’s a lot of variation, but futurism and art deco are popular.

Importantly, this group is not just the set of weirdos who find themselves outside both Red and Blue; it consciously rejects both Red and Blue for one reason or another (which we’ll look at later).

And ironically, it draws the most skepticism overall (from both sides) while also being the smallest threat to anyone outside of itself.

Why care about the Grey tribe?

It’s too small to sway elections, after all, and it’s too spread out to dominate the culture in any particular place. Why should you pay any attention to it?

For one, it’s dynamic. It’s different from the super-tribes because it produces ideas in direct response to the physical world, not through a cohesive ideology. New beliefs and values regularly conflict with existing ones, and there’s much internal disagreement and much synthesis. The models and mindsets and paradigms you find in the Grey tribe are fresh and often useful. They’re also just early. You could’ve known about Covid in January 2020 when all major media outlets were dismissing it as a non-issue. You could’ve known about the AI revolution over a decade ago. You could’ve known about Bitcoin—ugh, I don’t want to think about it.

Second, although I said Grey is least able to affect the outside world, that is slowly changing. Grey is home to some powerful people who are actively trying to make great, lasting changes in the world. Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Paul Graham, Vitalik Buterin, Tyler Cowen—when these people speak and write to the public, they echo talking points that have been making the rounds in the Grey tribe for years.

Elon wants to go to Mars; venture capitalists have founded an independent country in the Caribbean; Sam Altman, Mark Zuckerberg, and others are in the process of creating AI gods. These are neither Red nor Blue behaviors. Wouldn’t you like to know where all this is headed?

The Grey tribe is non-tribal?

The Grey tribe doesn’t behave like a tribe; it mostly fails at coordination. Why is that?

First, the Grey tribe is about something, which violates the signaling rule. There’s not much opportunity to signal loyalty when the few Grey tribe signifiers are things that people already think are good in themselves. Oh, you want a smaller State and greater individual liberties? Ok, but why? You could have any reason. [Insert joke about libertarians being pedophiles.]

The other factor is that these people usually don’t want to signal group membership: the Grey tribe is made up of people who are against tribalism (either explicitly or implicitly, which I’ll cover below).

Feeble coordination

What does it look like for a tribe to fail at coordination? Well, notice how the Red and Blue tribes can get their people into the greatest positions of power in the free world; the Grey tribe has never been able to do this. The Red and Blue tribes will rush to defend a fellow member who’s been publicly wronged; Grey tribe members mostly let each other fend for themselves. Red and Blue will hop onto a culture war angle together by the tens of thousands. Remember that week when Trump and Vance were “just weird?” Remember “What about her emails?” Oh, maybe they are weird. Maybe the emails were a big deal. But my point is those memes spread quickly through the whole Western digital world, and the Grey tribe has never created a meme that most ordinary people have to contend with.

There’s one more level to our analysis: many in the Grey tribe already understand the importance of coordination and the utility of tribalism as a means to that end. It’s all game theory, after all, which is one of the things Grey-tribers nerd out about. But they still value free thought and free speech and individualism. So it looks a lot like they’ve given up their ability to affect change in the world, in favor of these other things.

But, changing the world is often something they often care quite a lot about! What’s their answer to this problem?

Now it’s useful to look at some different subgroups within the Grey tribe: they have different reasons for dropping out of Red and Blue, and they have different answers to the problem of group coordination.

Index of some non-tribal tribes

All of the groups I’ll describe below can be lumped into the Grey tribe, but they’re different enough—in origins, values, and preferences—that they’re worth looking at separately.

1. Libertarians

This is the most obvious subset of the Grey tribe. Libertarians are defined by their belief in maximizing or almost maximizing the personal freedoms of individuals—whether because they hold it as a moral principle, or because they believe it’ll result in utopia, or because it’s what the founding fathers would’ve wanted, or some other justification.

Libertarians are invisible. The last time one was represented in popular culture was 2015, and that was a comedy.

1.1 Why they left Red and Blue

Libertarians reject both of the major tribes because they see authoritarian tendencies in each. This is not only a political difference but a fundamental value difference. Both Red and Blue appeal to “freedom” when it serves their interests but advocate for more top-down control when it doesn’t. For Red and Blue, freedom is an instrumental value in service to greater values. For libertarians, freedom is more like an ultimate/terminal value.

Often libertarians don’t appear to have left Red or Blue at all. Sure, the Blue tribe hates the word “libertarian” and thinks it means “Red tribe person who’s trying to trick me,” and the Red tribe only likes libertarians until they start hearing their actual views. But if libertarians don’t talk about politics a lot, their live-and-let-live principle allows them to blend in with either culture.

1.2 Their answer to the coordination problem

Libertarians do not coordinate well, and that’s why their political party is negligible despite championing policies that most US citizens would readily say they want (for example, federal legalization of weed).

We do see temporary flare-ups of coordination in opposition to certain things other tribes are doing. This is less like the coordination of a clan that lives and acts in sync with each other and more like the fleeting partnership of hired mercenaries.

- The so-called New Atheists had a whole movement in the early 2000s, collectively opposing Christian hegemony at home and Islamic fundamentalism abroad. They had activists and authors and comedians. They had cultural messaging. But now? George W. is gone, Republican presidents no longer talk about Jesus, and Islamic terrorism isn’t the national threat it used to be. Certainly not all members of that movement were libertarians, but it was a fundamentally libertarian movement: calling for greater separation of church and state, and opposing a foreign religion mainly on the grounds that practitioners of that religion were threatening others’ personal freedoms.

- In the 20-teens we had the so-called Intellectual Dark Web, a loosely collaborative group of public intellectuals and their followers. What drew them together was, to paraphrase their words, an earnest belief in the power of free dialogue to uncover truth. But what specifically drew them together in 2015 was their opposition to Blue-tribe censorship and cancel culture. But now? Well, you can only get so many podcast episodes out of the topic of free speech. “We like it, we believe in it.” Then eventually you just disband and go back to talking about the other things you like.

Movements like these are short-lived, either because they have a concrete goal that gets achieved, or because, in the absence of a concrete goal, there just isn’t much to do being against a particular thing.

1.3 Example

Reason.com is an archetypal libertarian publication. They’ll dutifully remind you of the standard libertarian position on anything that happens in the world on any given day.

2. Techno-optimists

Techno-optimists are defined by the belief that the solutions to society’s problems will come via new technology. With better tools, more available resources, and more abundant clean energy, we’ll eventually either develop a real utopia or at least upgrade to grander and more ambitious problems to solve. They want to remake the universe in man’s image: space travel, terraforming, Dyson spheres. They want to remake man in man’s image: human advancement through cybernetics and/or gene therapy, with the aim of increasing capability and lifespan and decreasing suffering. Some of them also want to make an “AI god”—a superintelligence that will solve our problems and organize our civilization more effectively than we could ever do on our own.

This characterizes most tech startup founders and the venture capitalists who fund them. And it includes the Effective Accelerationism movement, which is primarily about building that AI god.

2.1 Why they left Red and Blue

Technology often solves the same problems that tribal coordination does, and often its solutions are seen as better, more benevolent, more utilitarian. Techno-optimists view tribalism as a civilizational stage that we are now outgrowing.

For example, the technologies involved in mass production, global banking, global shipping, and the military superiority that protects that shipping, give us a trustless system of global trade—”capitalism.” You can buy almost anything from almost any seller at an agreed-upon price, and you’ll receive what was offered. Buyer and seller don’t have to know anything about each other—the source their coordination is not tribalism, but rather shared trust in this powerful system that manages free trade.

But Red wants protectionism for good ol’ honest manufacturing jobs, and Blue wants Amazon to be punished for outcompeting cute independent bookstores, etc. The techno-optimist points out the exponential growth in global prosperity and the all-time lows of global poverty and can’t understand why so many people hate this system of free trade.

This is the pattern of many conflicts that frustrate the techno-optimist: They notice Thing is too low/high; they invent a system to make Thing way higher/lower, their invented system replaces the older traditional “human” system, and people hate it because something unmeasured was lost. “But you wanted this!”

This goes all the way back to the invention of agriculture sustaining larger populations but also making people malnourished, greedy, and neurotic. The techno-optimist says, “No problem, I’ll just measure and manage those things too from now on,” while Red and Blue try ever harder to force them into retirement.

2.2 Their answer to the coordination problem

This is covered above, because “alternative ways of solving the coordination problem” is exactly why techno-optimists conflict with Red and Blue in the first place.

They hope for greater technological breakthroughs that facilitate coordination without tribalism—and without the falsehoods, conflict, and suffering that come with it.

2.3 Example

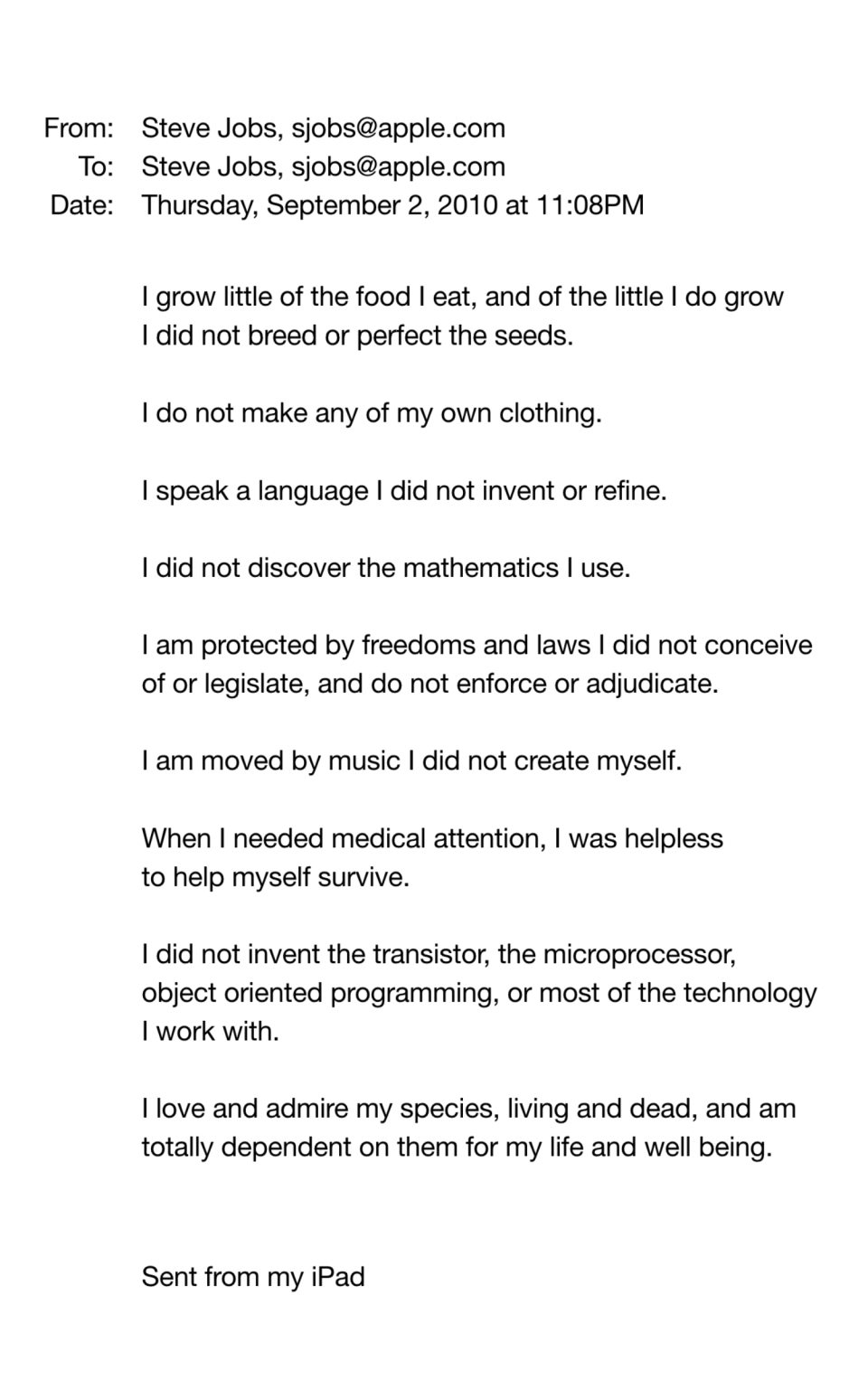

Tech founder and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen wrote a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” which covers all the main points. Elon Musk is by far the most well known techno-optimist. Also, this note from Steve Jobs illustrates the same ethos and especially shows its humanist roots:

3. Bay-Area rationalists

The Bay-Area rationalist movement is a philosophical development that I’d describe as “being-concerned-about-cognitive-biases, dialed up to 11.” It comes with a whole framework on what truth is, what belief is, and the roles of science and logic in human thought.

I include “Bay-Area” because that’s where the movement originated in the early 2000s, and it’s distinct from the original European “Rationalism” philosophy of the Enlightenment.

These are people who tend to be highly analytical, with high openness-to-experience personalities. They put a lot of effort into mitigating their natural cognitive biases in order to make the best possible decisions and thereby succeed in whatever their aims are (often the kinds of grand, humanity-saving aims that are characteristic of Silicon Valley).

This group includes many superforecasters—the term coined by poli-sci professor Philip Tetlock for people who are especially good at predicting future events based on available information. It also includes some professional gamblers, members of the Effective Altruism movement, and AI-safety activists.

3.1 Why they left Red and Blue

Rationalists are non-tribal because they see a danger in all forms of “groupthink.” They have even created formal systems to show exactly how and why supporting your tribe is deceptively different from honestly describing reality (like EY’s Professing and Cheering and Zvi’s simulacra levels).

Bay-Area rationalism is a movement about how to think. There is plenty of debate on what to think, about popular topics like AI timelines, political philosophy, and new developments in science, but there’s really no object-level opinion that could either confirm or deny one’s status as a “rationalist.” This is opposite to how most tribes work.

This is also where that high-decoupling trait comes in: the rationalist doesn’t care very much how their opinion comes off; they don’t care what it’s associated with; they don’t care if it sounds like something bad or dumb—it’s true, and they will gladly either convince you of that or have you convince them otherwise.

You can infer that while the rationalists have their reasons for rejecting the Red and Blue tribes, Red and Blue aren’t exactly begging them to stay.

3.2 Their answer to the coordination problem

Rationalists are loosely held together by a shared belief in objective reality (or at least the possibility of predicting what we experience as objective reality). And mostly they share belief in the efficacy of the scientific method and probability theory in helping one make good predictions—and thus good decisions. All of this is quite vague and does little to facilitate coordination.

A more effective coordination mechanism is the depth of canon rationalist literature and jargon. If one uses a lot of internal concepts in their communication, it shows they’ve read a lot of the core rationalist writings, which means two things:

- They’ve invested a lot of time already.

- They’re the kind of person who likes that dense, highly analytical, sometimes dry form of writing, which has implications for other aspects of their personality (i.e. being Internet-autistic, or actually autistic: in either case, being uncomfortable with falsehood and manipulation).

These happen to be decent ways to evaluate someone’s good faith / trustworthiness.

There’s also occasionally coordination around individual personalities—i.e. cults. Yes, there’ve been a number of cults.

3.3 Example

Blogger Jacob Falkovich is an especially approachable rationalist.

If you have a friend who refers to “Bayesian reasoning” or “utility functions” in everyday speech (and chances are, you do not), this is their group.

4. Postrationalists

The postrationalists are people who believe they have understood the Bay-Area rationality movement but find it wrong or unimportant for one reason or another. They believe rationalists don’t pay enough attention to aesthetics to create enjoyable lives for themselves, or don’t trust their intuitions enough to make good decisions in certain contexts, or put too much emphasis on being correct about the physical world and not enough on being happy. (Most rationalists say they already account for these things, so there’s constant disagreement.)

While rationalists might hold their object-level beliefs loosely and show a lot of variance there, postrationalists vary in virtually all dimensions of life: not only in beliefs, but in personality, age, spirituality, and life purpose. There are meditation masters, farmers, devout Catholics, engineers, hippies, preppers, etc.

Postrationalists mainly organize on X (Twitter) and, fully aware that they’ll be misunderstood by the Red-Blue mainstream, in private group chats.

4.1 Why they left Red and Blue

Postrationalists have typically gone through a rationalist or atheist phase wherein they rejected some fundamental thing that their whole tribe believed in—whether a religion or a political philosophy or just a complex moral system. Having seen that pattern once, they recognize it in other places, including mainstream cultural tribalism.

Postrationalists are postmodern—not in the Jordan-Peterson-alarmist sense, but in the original sense of being skeptical of all meta-narratives and absolute sources of meaning.

4.2 Their answer to the coordination problem

Despite all the above, Postrationalists usually want to belong to a tribe and enjoy it as humans naturally tend to do. This is a tricky thing, because they can’t ignore their original reasons for rejecting common sources of meaning.

non-hostile critique of many contemporary reactionaries: you cant go home again

societal exposure to systematic thinking is hard to reverse and its probably not desirable to do so

the only way past modernitys denial of the sacred is forward, to an adult recreation thereof

— eigenrobot (@eigenrobot) March 23, 2023

Postrats sometimes turn back toward religion, mysticism, or other grand narratives, but unlike ordinary believers, they only participate because they perceive the utility of it (and the poverty of its absence), not because “that supernatural event from 2000 years ago actually happened.” The latter is the kind of answer that a true believer gives, and it’s not about utility or aesthetics. This causes some degree of tension for the postrat: it’s hard to be tribal when one knows one is being tribal.

4.3 Example

X personality Eigenrobot is an archetypal postrationalist.

5. Machiavellians

This is a loaded term—I don’t really mean pathologically manipulative people. I mean people who behave according to the ideas Niccolò Machiavelli laid out in The Prince: power as distinct from morality; the practical advantages of amorality; life adhering to the laws of reason rather than of justice.

These people have not necessarily read The Prince, but the ideas therein were so influential in Western civilization that they show up in many places today. We have newer books like Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion or The 48 Laws of Power, and we have public figures and influencers who are all about “doing whatever it takes” to “get your money up” or “win that next client.”

All brands, groups, and people who are focused on getting rich, whether through crypto trading or entrepreneurship or multi-level marketing or whatever, tend to share a common life philosophy.

Machiavellians have no loyalty to any tribe, but they’ll sometimes pretend to (that’s simulacrum level 4, for what it’s worth).

5.1 Why they left Red and Blue

Maybe it was personal ambition, frustration, or a contemptuous glimpse at herd behavior from the outside. Maybe it was just “high individualism,” if that is in fact a fundamental psychological trait.

Machiavellians see tribalism as something with which to manipulate other people. They see the potential usefulness in signaling that you’ve joined this-or-that tribe, but actually joining the tribe, with conviction, is inviting yourself to be manipulated.

The main reason to not follow politics is that it makes you ideological (and nowadays, extremely ideological), and extreme ideology is not good for judgement and rationality.

I could not care who wins the elections, I will try my best to prosper in any circumstance.

— LifeMathMoney | Real Advice (@LifeMathMoney) July 23, 2021

5.2 Their answer to the coordination problem

Machiavellians have shared goals—not common goals, but shared goals. They all want the same exact thing for themselves, and that’s the main thing tying them together. This makes for terrible coordination. Communities under this banner are notoriously low-trust. Everyone is there to learn, hopefully not get scammed, and maybe scam someone else.

If anything, Machiavellians might enjoy the advantages of tribalism (with others, not with each other) simply by lying: signaling membership in something they don’t really believe in.

5.3 Example

Who is an archetypal Machiavellian? That’s uniquely hard to say, because it’s kind of a core tenet of Machiavellianism that you should appear less powerful/savvy/ambitious than you really are. Machiavellians who are really overt about what they’re doing usually write under pseudonyms, like Corporate Machiavelli or BowTiedBull.

I can think of one named example, and that’s Jay-Z, who has done us the service of coming right out and endorsing The 48 Laws of Power in interviews. There’s no ambiguity about whether he consciously sought his power and money or “just stumbled into it.” He’s practiced Machiavelli’s principles better than most: the public image he’s crafted and the decisions he’s made throughout his career have made him an extremely powerful and influential person.

Summary

There’s a growing cultural space that’s neither occupied by the Red nor Blue tribe. It’s full of interesting people who are disillusioned about the two super-cultures and the whole paradigm in which they fit. What these people gave up in tribal coordination, they gained in greater freedom to determine their own values and lives. The result is a fresher, more dynamic arena of human activity and, in the best case, maybe the gradual beginnings of a second Renaissance of human development in philosophy, psychology, art, and technology.

But the thing I most want to communicate is that they exist at all. Elon might stand next to Trump on stage, but he isn’t Red tribe. The quiet engineer who showed you “this weird psychiatrist blog” might vote blue, but she isn’t Blue tribe.

Pingback: On Credibility: Whom to trust on the Internet - Patrick D. Farley