Denial of Death is the 1973 summation of anthropologist Ernest Becker’s life’s work studying human nature, building upon the work of the great psychologists of the 20th Century. It basically aims to be a grand unifying theory of psychology, and against all odds it kind of succeeds.

I came across DoD on a forum under the topic, “books that drastically changed your life” or something like that. Since then I’ve only encountered a few other references to this book in my life, coming from quite different types of people but all glowing. There was the late, great Norm Macdonald, a brilliant comedian known for his esoteric disposition and his ability to create humor out of anything—he references the book as pretty important to his worldview. There’s my yogi friend who’s very into intuition and spirituality and swears by it as a way to understand herself. And there’s me—analytical, materialist—who has also found tremendous value in it. I hope you will, too.

TLDR

Becker’s thesis is that humans have a paradoxical dual nature (divine vs. animal), the tension of which causes us to experience psychological terror. The presence of that terror makes us “partialize” the world by embedding ourselves within relatively safe pockets of it—we set up a game-within-the-game to play. This lets us pursue our “heroic” projects without having to face the scary limitations and risks that come with our animal nature. The pockets we hide ourselves in include the behaviors and thoughts we adhere to, so all psychological neuroses as well as “normal” human character are contextualized as various responses to a deep fear of that animal nature. This context gives us a new schema for understanding neurosis, mental health, personality, etc.

I promise that this book is not all fluffy academic jargon. This is a book that’s heavy with new concepts, but all of the above are meant to pertain to concrete things that you and I experience.

If there’s a call to action to be gleaned from this, it’s something like: You should seek to take in more of life, more chaos, but without destroying yourself. And you shouldn’t judge or condemn people who live simple lives or rely on blatant repressions—their experience is as heroic as yours.

Context of the work

Cultural Anthropologist Ernest Becker wrote this Pulitzer Prize-winning book at the end of a long career as an anthropology professor. Published in 1973, this book spoke to one consequence of the emerging secular pluralism in American society: the old structures of meaning were losing their relevance, and their replacements were being found inadequate. Becker explores the psychological needs and weaknesses that appear in the absence of trusted grand narratives, elegantly tying them all back to a primal fear of physical death and a need to achieve symbolic immortality through actions that are universally worthwhile.

What you’ll enjoy

One of the first things a reader will notice is that this work is way more ambitious than anything we associate with the word “psychology” today. Thinkers who are vexed and disappointed with modern psychology—the endless parade of tiny particular claims seemingly made for no reason other than to get papers published, only to fail replication a couple years later—can fully indulge in something which is far on the other side of the spectrum. There’s almost a taboo fascination reading something whose claims are so far-reaching. I’m not exaggerating when I say this book aims to be a Grand Unifying Theory of human psychology. If that sounds familiar to you, let me confirm that yes, Becker writes extensively about Sigmund Freud and his ideas. While conceding that much of it was wrong and that Freud lived in what we’d call a happy death spiral of his theories, Becker asserts that Freud was on to something. But the end product is far different from Freud’s work.

Does it succeed at that? It’s complicated. If I hadn’t read the book, I’d primarily be wondering, “Ok, psychology is a science; does this book give me any scientific models that have more predictive power than the models I’m currently using?” I think the answer is, “Yes, slightly, with caveats,” but that’s not where the real value comes from. This work really shines as a way to simplify and unify many psychology concepts that you already know (and maybe a few more). A theory which predicts all the same facts while being much simpler than the standard theory, is a better theory.

I see the main thesis of this book as a kind of alternative coordinate system—you could describe modern psychology as painstakingly trying to describe a spiral shape in cartesian coordinates, and then along comes the polar coordinate system where it’s trivially easy.

The system of ideas described in this book have become fundamental to how I understand myself, others, and culture at large. It is a really elegant system.

The other thing I deeply appreciate about the book is what it doesn’t say about death. This is not another new-age just-so solution to the terror of the human condition. It doesn’t tell you to “meditate on death so you can grow to accept it” or “kill your ego and be one with the universe.” It also doesn’t tell you, like the Greek philosophers would’ve, that after a life virtuously lived you should be able to greet death with satisfaction. For reasons I won’t go into now, I reject those view and believe that no, death is actually really bad, and viewing it as anything else is a coping mechanism.

This book pulls no punches and does not really prescribe a solution. Readers should keep the Litany of Gendlin in mind: If the book’s thesis is true, then you are already living under these conditions; knowing about them can’t hurt you further. And in this case I think readers will find themselves much better armed to understand themselves, others, and society, and therefore more easily effect marginal change for the better.

What you’ll dislike

This isn’t an easy read. That’s partly because Becker’s style borders on cryptic academic jargon at times (though it could definitely have been worse, and as concepts click into place, old passages become more clear). It’s also because the subject matter is heavy. A given paragraph could be making implications about every decision you’ve ever made up to this point in your life. I found that a lot of reflection time was needed, and I took a ~6-month break in between reading the first and second halves.

Two other complaints I have are that the order of chapters is kind of dizzying (more on that below) and that there is more content about Freud than most readers will really care about.

About this outline

My outline of this book is long because the book covers such a breadth of topics. I’ve left the more important sections long and tried to cut down the others. I’ve also switched up the chapter order to present the concepts in a more learnable way—you’ll thank me for this. The way Becker organized this book is not optimal for learning the concepts, because he also aims to do a kind of sequential look through Freud, his students Carl Jung and Otto Rank, and some other psychologists and philosophers. I often had the experience of, “Ok, this concept is exactly the same as that earlier one, but with a new perspective.” I think the value of this book is in the concepts that are laid out and not in how they originally evolved from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory.

Another way to save time would be to skip the quotes (there are a lot, though they are quite poetic). I’ve summarized what I felt were the most important points in my own words. I also point out where the quotes belong to other psychologists, presented by Becker; he does this fairly often.

Chapter 1 – Introduction: human nature and the heroic

The gist of this chapter is that humans need to engage in some kind of heroism in their lives. Replace “heroism” with “meaning” or “purpose” and it all basically matches Becker’s point. This is a key concept throughout the book.

Then we land on “cultural heroics”: When we’re unsure what kind of heroism really matters, or afraid to do the heroism we think matters, we settle for culturally-sanctioned hero projects. We defer to our culture to decide what is meaningful:

- “It doesn’t matter whether the cultural hero-system is frankly magical, religious, and primitive or secular, scientific, and civilized. It is still a mythical hero-system in which people serve in order to earn a feeling of primary value, of cosmic specialness, of ultimate usefulness to creation, of unshakable meaning.”

- “Human heroics is a blind drivenness that burns people up; in passionate people, a screaming for glory as uncritical and reflexive as the howling of a dog. In the more passive masses of mediocre men it is disguised as they humbly and complainingly follow out the roles that society provides for their heroics and try to earn their promotions within the system: wearing the standard uniforms—but allowing themselves to stick out, but ever so little and so safely, with a little ribbon or a red boutonniere, but not with head and shoulders.”

Chapter 2 – The terror of death

“The revival of interest in death, in the last few decades, has alone already piled up a formidable literature, and this literature does not point in any single direction.” Becker describes two common schools of thought with regard to the fear of death:

- Healthy-minded argument: fear of death can and should be overcome

- “From this point of view, fear of death is something that society creates and at the same time uses against the person to keep him in submission.”

- Morbidly-minded argument: fear of death is innate

- “That nevertheless the fear of death is natural and is present in everyone” … “the worm at the core”

Becker buys into the morbidly-minded argument: fear of death comes with the territory of being human. He points out that this aligns with the need for self-preservation, so it makes sense in light of evolution. Yes, some will claim they lack this fear, but Becker attributes this to a successful repression: “[From Zilboorg:] A man will say, of course, that he knows he will die some day…and he does not care to bother about it – but this is a purely intellectual, verbal admission. The affect of fear is repressed.”

William James, Sigmund Freud, and Freud’s students also took this view.

Childhood terror

Becker argues that we all encounter tremendous fear as children when we come to understand our own mortality. He focuses not so much on the single fact of knowing you’re going to die, but more on the surrounding facts: all the ways your physical body determines and limits your experience. “I think it is important to show the painful contradictions that must be present in it at least some of the time and to show how fantastic a world it surely is for the first few years of the child’s life.”

The argument goes: a child observes that he does not always have control over his immediate environment. He seeks to understand how the whole system works, but it’s extremely complicated to him. Yelling and crying works, except sometimes when it doesn’t. Speaking works, except when mysterious “reasons” and “circumstances” unexpectedly break his model. A little later on, he learns that not only is he contingent on unpredictable physical systems, but the parts of that system on which he’s most contingent (his parents) are equally contingent themselves.

It’s hard for me to disagree with this setup when 1) I try to imagine the stress of having my priors obliterated as frequently as a child’s are, and 2) I recall instances where I’ve witnessed people experience extreme terror, and nearly all of them are children.

Maturation and the “disappearance” of the terror

As we become adults we stop experiencing such panic. One would assume it’s because we figure out how the world works. Becker sort of flips this around: part of the work we do in that process is to shrink our world into something that we can easily figure out.

- “Man cuts out for himself a manageable world: he throws himself into action uncritically, unthinkingly. He accepts the cultural programming that turns his nose where he is supposed to look; he doesn’t bite the world off in one piece as a giant would, but in small manageable pieces, as a beaver does. He uses all kinds of techniques, which we call the “character defenses”: he learns not to expose himself, not to stand out; he learns to embed himself in other-power, both of concrete persons and of things and cultural commands; the result is that he comes to exist in the imagined infallibility of the world around him.”

Much more on this later.

The Nature of morbid terror

Here, Becker gives a philosophical embellishment to that kind of terror. He describes it as “Man’s dual nature”: Humans are animal, but we are the only animal that knows it is mortal. This gives rise to aspirations of divinity, says Becker. We know what it means to be powerless, so we imagine having infinite power. We know what it means to expire, so we imagine living forever. We care about right and wrong, but not just so we can cooperate with our peers; we want to take “right” and impose it on the entire universe, despite being physically incapable of doing that.

- “He is half animal and half symbolic…This is the paradox: he is out of nature and hopelessly in it…He sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever.”

Chapter 4 – Human character as a vital lie

This chapter is further elaboration on the “character defenses” mentioned in the quote above.

“The Jonah Syndrome [from Maslow], then, seen from this basic point of view, is “partly a justified fear of being torn apart, of losing control, of being shattered and disintegrated, even of being killed by the experience.” And the result of this syndrome is what we would expect a weak organism to do: to cut back the full intensity of life.”

Becker claims that we shy away from life, in so many ways, in order to avoid the dangers it contains. This is not just a physical shying away (i.e. staying near the campfire), it is also experiential shying away: We cannot think too much about the vast field of possible experiences before us, because it is overwhelming. “Most of us—by the time we leave childhood—have repressed our vision of the primary miraculousness of creation.”

Personally, I’ve noticed this kind of thing as I continue to grow without (currently) any major life commitments. There are a lot more possible lives that I could go live. Very different, numerous possible lives. Should I retire to a farm when I’ve saved enough? Should I find a way to live in Europe for a year? Should I do the big city rat race until I’m 40? Should I be more involved politically? And on what issue? Should I get really into meditation?

And then a part of me would say, “No, you don’t like farms. No, your career goals aren’t in Europe,” but according to Becker that is exactly the repressive tool of “human character” rearing its head—that somehow I am incompatible with every possible lifestyle except the one I’m currently in. I make decisions according to expected utility, but couldn’t by utility function be changed by a few more formative experiences? What if I’d have the same tastes as the world’s most satisfied farmer, and the only way to realize it is to go through the trouble of “switching lanes” and trying it? These are the questions we protect ourselves from asking. They are debilitating if we ask them too often.

The fear of life

Becker describes the “Fear of life” as the following:

- “[Mankind is] an animal who has no defense against full perception of the external world…an animal completely open to experience. Not only in front of his nose, in his umwelt, but in many other umwelten. He can relate not only to animals in his own species, but in some ways to all other species. He can contemplate not only what is edible for him, but everything that grows. He not only lives in this moment, but expands his inner self to yesterday, his curiosity to centuries ago, his fears to five billion years from now when the sun will cool, his hopes to an eternity from now. He lives not only on a tiny territory, nor even on an entire planet, but in a galaxy, in a universe, and in dimensions beyond visible universes.”

I’m not sure it’s a useful label because, as he goes on to explain, it’s not really different from the fear of death, just another aspect of it. We “fear life” in the sense that we fear being totally open to experience, because the scope and depth of our experiences threaten to overwhelm us and make us lose ourselves. And the only reason that’s bad, really, is because in our lost, ungrounded state we might actually lose control of our physical environment and thus lose our lives—our very ability to experience anything. It’s a perverse deal: infinite possible experiences, but if you reach for them all with abandon, you’ll lose everything pretty quickly.

I hope I’m not being too woo/conceptual here. Becker references the schizophrenic homeless person who is fully engaged in some set of ideas that are extremely interesting to him, even as his physical body suffers. Or, think of a high-openness teenager who gets a bit too excited about the idea of leaving her small town, so she travels across the world to “find herself,” and gets robbed on the first day of her trip, putting her in serious danger. Or the risk-averse nerdy guy who decides to subvert his character for one night and try psychedelics, and then ends up on a bad trip and tries to harm himself.

Yet, it is possible to spend days in heady thought without becoming homeless. It is possible to get across the world from your small town in less than a day and have a really great time over there. It’s possible psychedelics could permanently make you a happier person. What Becker calls the “character lie” is that which says, “You just don’t do things like that.” The character lie is based on one’s native culture and one’s peers: it’s what is “normal.” And it’s a lie, because there are so many other “normals” one could have if one wanted to.

Becker defines psychoanalysis as the study of this self-limitation (the character lie) and its cost.

Chapter 7 – The spell cast by persons – the nexus of unfreedom

Here we get into a more complex kind of repression that people employ. Becker borrows and reframes a concept from Freud—transference. In Becker’s framing, transference is when we find some comfortable Other and make it stand in for the entire universe for us. He gives two types, but later explains that “transference” and “the character lie” are not really different things—they are different ways of embedding ourselves into safe systems and using “borrowed powers” to face our world without fear.

Group leaders

People use their authorities as transference objects: The leader represents the world to us, and represents our concerns to the world. All will be okay as long as we obey the leader. And if it’s not okay, that will be the leader’s fault, and they will atone to the rest of the universe for it on our behalf.

- “He blows the physician up larger than life just as the child sees the parents. He becomes as dependent on him, draws protection and power from him just as the child merges his destiny with the parents, and so on. In the transference we see the grown person as a child at heart, a child who distorts the world to relieve his helplessness and fears”

- “The part of the father is transferred to teachers, superiors, impressive personalities; the submissive loyalty to rulers that is so wide-spread is also a transference of this sort.”

Becker moves on to what happens when this transference becomes too complete:

- Leaders can sanction taboo behaviors, and people will indulge without responsibility. “This, then, is another thing that makes people feel so guiltless, as Canetti points out: they can imagine themselves as temporary victims of the leader.”

- The leader can then use this “suspended guilt” to bind them closer to him. If they leave his domain, they are subject to outside judgment for their acts.

- And that’s how we get cults. “We are faced with the even more astonishing conclusion that homicidal communities like the Manson “family” are not really devoid of basic humanness. What makes them so terrible is that they exaggerate the dispositions present in us all.”

Becker also points out an interesting dynamic in leadership that I’d never considered before. The transference actually goes the other way, too. The leader uses his following as a stand-in for the universe. If he can control the group and be a hero in the eyes of the group, then he believes himself a hero who’s in control, period.

- The group he leads serves as a smaller, safer world for him to conquer: “He is not just a naturally and lustily destructive animal who lays waste around him because he feels omnipotent and impregnable. Rather, he is a trembling animal who pulls the world down around his shoulders as he clutches for protection and support and tries to affirm in a cowardly way his feeble powers.”

- “The qualities of the leader, then, and the problems of people fit together in a natural symbiosis.”

Of course this kind of transference is doomed, because the leader doesn’t actually have that kind of mastery over the universe: “When the leader dies the device that one has used to deny the terror of the world instantly breaks down; what is more natural, then, than to experience the very panic that has always threatened in the background?”

Relationships

Perhaps the most controversial part of Becker’s thesis (but, I find, one of the most fascinating) is the idea that masculinity and femininity are different sides of the transference equation. His definitions of masculinity and femininity would seem narrow-minded if he prescribed them onto men and women respectively, but in fact he doesn’t do this. Becker has lots to say about people who are playing the masculine role but doesn’t prescribe anything for men. I’m going to do my best to summarize these terms as Becker uses them:

- Masculinity is that which seeks to engage with chaos, conquer it, and bring it into oneself. It’s Freud’s concept of Eros. It’s the heroism Becker referred to in Chapter 1, and it’s the urge to stick out from one’s context and be an individual force in the world. Ultimately, the masculine would like to remake the universe in its own image.

- Femininity is that which seeks to find something stronger than oneself, endear oneself to it, and join it, providing some kind of value in exchange for protection and borrowed power. Ultimately, the feminine would like to merge and achieve perfect unity with the rest of the universe.

The reason I find this fascinating is because, in light of all this talk about borrowed powers and human fragility in a chaotic physical world, Becker has pointed out reasons for masculine and feminine behavior that go beyond reproductive success. I’ve been convinced (this is probably one of the most uncommon beliefs I hold) that even if humans were asexual, some of us would be more masculine and some would be more feminine, because these are two fundamental responses to chaos, and we tend to benefit from specializing in one or the other.

We can see how this applies to the tension of wanting to stand out from one’s culture as a hero vs. wanting to belong to the culture and enjoy its protection. It’s less interesting to me that males do more of the former and females more of the latter, and more that we all do both, and we all have an ideal proportion of each (more on that later).

That being said, yes, we can look at the typical traditional heterosexual relationship and see this pattern of transference. He goes out into the world and “conquers” some of it; brings home value from it; protects her. She “belongs to” his house; helps him; relies on his protection. If it’s really a traditional relationship, this protection goes beyond the physical: there are whole categories of worldly concerns that she doesn’t have to bother with, because those are “his business.” So long as she is a hero within his world (a “good wife”), she is good, period. Never mind the work she could be doing on cancer research, AI risk, etc.; the purpose of transference is to block those possibilities out. Likewise! He gets to play the hero for her. As long as he provides for her, he is generous (never mind the starving people elsewhere in the world). As long as he keeps her comfortable, he is a good steward of his domain (never mind climate change).

In this way both parties use the other to minimize the worlds in which they could act out their hero projects.

Beyonds

This is another big concept; if you take only one concept from this whole summary, it should be this one. For Becker, one’s “beyond” is the lifestyle space one finds oneself in once transference happens. For the cult follower, it’s the cult. For the strictly traditional couple, it’s the household. For the middle-management careerist (Venkatesh Rao’s “Clueless”), it’s the company. It’s the default place where one looks, when one looks “beyond oneself.” It’s what’s “out there” for us—the (limited!) space in which to find some chaos and bring it into order.

Most people have more than one beyond, but not too many. Career, romantic relationship, hobby community, religious community, etc. Becker points out that there are tight beyonds and open beyonds, with the expected tradeoffs.

And Becker points out that people choose different beyonds for themselves, according to what appears to be a particular balance being sought. An obvious example: adolescents naturally start to experience more of that Eros/masculine drive to stand out and express themselves, so they move from smaller beyonds to larger: small town to big city, strict religion to open spirituality, biological family to loosely connected friend group.

- “You can try to choose the fitting kind of beyond, the one in which you find it most natural to practice self-criticism and self-idealization.”

A different example: Person A—shy, straight-A student, uncommitted career-wise—goes to grad school. They find themselves caring deeply about faculty drama, about recruiting new students to the program, and about being liked and respected by everyone there. They like the structure of adult education and find the prospect of graduating and moving on frightening. Person B—aggressive, ambitious, pragmatic—has a well defined career goal and needs grad school as a stepping stone. They don’t bother to learn their classmates’ names and only relate to the professors in order to secure useful future connections. They feel stifled and can’t wait to graduate. Grad school is serving as a beyond for Person A but not Person B, and that’s because of psychological differences that exist between them.

We could say Person B requires a more open beyond than Person A at this point in their lives. Grad school is a tighter beyond than entrepreneurship: there are more rules, more bounds, and consequently lower risks. We could dare to say Person B is more masculine under Becker’s definition. And, if we’re intent on getting predictive power out of this model, we could say Person B is more likely to be male, more likely to care about personal physical strength, more likely to score low on Big-5 neuroticism, and the like (more interesting correlations in later sections).

Again, this probably isn’t new predictive power, but the value is in the simplicity of the model.

- “You can ask the question: What kind of beyond does this person try to expand in; and how much individuation does he achieve in it?” When I meet someone new, I want to know what their beyonds are, and this is much simpler than piecing together a list of “Cares about X in Y context but not in Z context; is generally uncomfortable in W context, etc.”

Indulge me for a tiny bit of TV analysis (no spoilers). While I was reading this book I was watching Mad Men. I noticed that throughout the series, when Donald Draper would run into trouble with his romantic partner, he’d invest more in his career (and often shine). And when he was facing setbacks in his career, he’d invest in his relationship (to his partner’s appreciation). It was an oscillation between two beyonds—heroism in one was needed to bury the failures in the other. And, both were too stringent on their own, otherwise he would’ve remained in one or the other for the long run, as other characters did. I found these ideas very useful for analyzing dynamics like that, especially in my own life.

Choice of beyonds

When your beyonds are too tight, you feel stifled, like “one of the crowd,” and guilty for not living more true to yourself. When your beyonds are too loose, you feel overwhelmed and paralyzed with fear of failure.

Becker asserts that most people choose the “nearest” beyond to make their transference object: “Most people play it safe: they choose the beyond of standard transference objects like parents, the boss, or the leader; they accept the cultural definition of heroism and try to be a “good provider” or a “solid” citizen. In this way they earn their species immortality as an agent of procreation, or a collective or cultural immortality as part of a social group of some kind.”

Of course, all this helpful talk about finding beyonds that are just right is not a solution to the problem of morbid terror. That’s because when you realize that the boundaries you’ve set up for yourself are arbitrary, the heroism you achieve within those bounds loses its meaning. You are a well liked and productive member of your team at work, but is this really the team that will best equip you to change the world the way you want to? Is this even the best company to do so? If not, your self-image flips from “office hero” to “coward hiding from their purpose.”

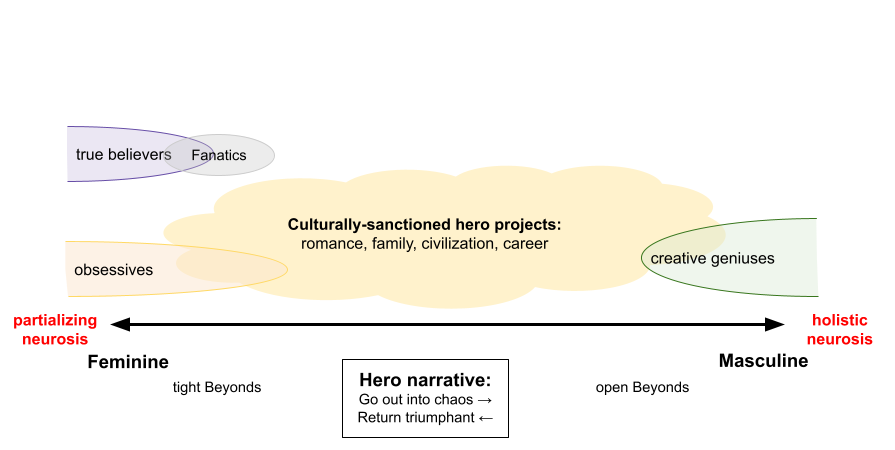

I made this graphic to keep track of my own understanding of beyonds: how they span a spectrum between “tight” and “open.” I noticed that the basic hero narrative could be thought of as taking little steps forward and back on this spectrum: confront a little more chaos than you’re used to, then return to your comfort zone. There are some concepts here that show up in later chapters. I also included the concepts of “True Believers” and “Fanatics” from Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer—more on that at the end.

Chapter 3 – the recasting of some basic psychoanalytic ideas.

Becker reinterprets a lot of Freud’s ideas (anality, Oedipal complex, penis envy) within an existential context. “Consciousness of death is the primary repression, not sexuality.” I think much of it is still a stretch, just as I think about Freud’s original descriptions. Becker does a better job of making us see this “primary repression” in everyday life in his later examples, so I will skip over Freud’s subject matter.

Chapter 6 – The problem of Freud’s character, Noch Einmal

This chapter is about how and why Freud was wrong in his attempted grand unifying theory. There is a lot of analysis about what Freud believed and what he feared at different points in his career, and how those pressures might have driven his research toward the direction of superstition. I don’t think it’s worth elaborating on here, but scholars of Freud would get a lot out of it. I think this chapter made more sense in the 1970s when Freud’s work was more culturally relevant.

Chapter 5 – The psychoanalyst Kierkegaard

It gave me quite a surprise to learn that the Christian Theologian Søren Kierkegaard has a whole chapter dedicated to him in this neo-Freudian book about death. Becker found that Kierkegaard, when writing about human character and behavior, landed squarely on some of the ideas above. He pulls content mainly from The Concept of Dread and The Sickness Unto Death.

This chapter starts Becker’s look into neuroses (mental illnesses). He mostly takes a back seat and channels Kierkegaard’s own concepts, adding on to them later. A core idea here is that the nature of the neurosis is a matter of how a person relates to their beyond, especially after realizing that it’s a culturally arbitrary beyond and isn’t really satisfactory.

In the later part I’ll comment on whether I think these idea are compatible with modern psychology.

The Fall and man’s dual nature

Becker notices that his account of the problem of man’s dual nature somewhat matches the Christian account of the Fall of man. In several places in this book, Becker speaks approvingly of Christianity without really endorsing it. More on that later.

- This is Becker’s synthesis, meant to apply to both frameworks: “Man emerged from the instinctive thoughtless action of the lower animals and came to reflect on his condition. He was given a consciousness of his individuality and his part-divinity in creation, the beauty and uniqueness of his face and his name. At the same time he was given the consciousness of the terror of the world and of his own death and decay.”

The Immediate man / Philistine

Here we start getting into a kind of list of archetypes that represent different neuroses. Becker says of the man who lives under the “character lie”: “[They] do not act from their own center, do not see reality on its terms; they are the one-dimensional men totally immersed in the fictional games being played in their society.”

Meanwhile, Kierkegaard wrote about the “immediate man,” whose identity is based on the cultural symbols immediately surrounding him: “He dies; the parson introduces him into eternity for the price of $10—but a self he was not, and a self he did not become… For the immediate man does not recognize his self, he recognizes himself only by his dress, … he recognizes that he has a self only by externals.” That is, K’s immediate man identifies himself only by the set of cultural symbols he wears.

“For Kierkegaard “philistinism” was triviality, man lulled by the daily routines of his society, content with the satisfactions that it offers him: in today’s world the car, the shopping center, the two-week summer vacation.”

Responses to Philistinism

Becker believes most people belong to the immediate man / Philistine category. What happens when they discover the pitfalls of their flawed identity projects?

The introvert

This is not the modern concept. Kierkegaard’s “introvert” is the person who realizes he is an immediate man and has contempt for it, believing he is something unique that others are not. We wants to see himself as special, but norm-breaking actions are dangerous: “It would be so nice to be the self he wants to be, to realize his vocation, his authentic talent, but it is dangerous, it might upset his world completely.”

What then? He imagines for himself a hidden identity that doesn’t really correspond to his actual life: “And so he lives in a kind of “incognito,” content to toy—in his periodic solitudes—with the idea of who he might really be; content to insist on a “little difference,” to pride himself on a vaguely-felt superiority.”

The self-created man

An alternative response is what Becker calls the “self-created man.” Seeing that all he’s accomplished is “cultural heroism,” and realizing that he is impotent to become something greater, he rebels against the whole system that kept him in such a box. “At its extreme, defiant self-creation can become demonic, a passion which Kierkegaard calls “demoniac rage,” an attack on all of life for what it has dared to do to one, a revolt against existence itself.”

- This is meant to cover anyone whose bitterness over their own impotence turns into vengefulness against the world. People who start mass movements against the status quo because they couldn’t attract a partner, or because they can’t earn more money, or because their country is in debt and they failed art school.

Similar to this is prometheanism: those who embark on exploration for its own sake: “It, too, is thoughtless, an empty-headed immersion in the delights of technics with no thought to goals or meaning.”

- When I think prometheanism, I think outer space. I don’t think Elon Musk fits this archetype, because he does have a goal he believes in, but I think many of his fans who uncritically ride the “Space travel is badass!” hype do fall into this category.

- There’s also the Silicon Valley flavor of this: founders who conquer the world with their app, make billions… and do what with it exactly? What was it all for? There is a type of person here who appears to chase wealth just for the sake of seeing a number go up on a screen—as a distraction.

The “cipher in the crowd” (depressive)

A person is depressed when see both the triviality of their beyond, and its persistent necessity, so they remain in it and try to live without meaningful heroism.

- “[Kierkegaard:] by becoming wise about how things go in this world, such a man forgets himself…does not dare to believe in himself, finds it too venturesome a thing to be himself, far easier and safer to be like the others.”

- “[Kierkegaard:] this kind of man is paralyzed; he won’t engage with possibility, so he is stunted and can’t really do anything”

- [Kierkegaard:] “[in the depressive] either everything has become necessary to man or everything has become trivial.”

- Becker amends this thought: “Actually, in the extreme of depressive psychosis we seem to see the merger of these two: everything becomes necessary and trivial at the same time—which leads to complete despair.

- “The depressed person avoids the possibility of independence and more life precisely because these are what threaten him with destruction and death. He holds on to the people who have enslaved him in a network of crushing obligations, belittling interaction, precisely because these people are his shelter, his strength, his protection against the world.”

Depression is what we’d call the symptom of this, regardless of the composition of its causes.

Infinitude’s despair (schizophrenic)

Becker frames the schizophrenic as having the opposite response to their beyond. They deny its necessity, and deny that any hero-project they invent must be trivial. So they go looking far, wide, and deep, for heroism in life’s infinite possibilities. Recall the danger of losing oneself.

- “What we call schizophrenia is an attempt by the symbolic self to deny the limitations of the finite body.”

“What really is lacking is the power to … submit to the necessary in oneself, to what may be called one’s limit.” - for K, it was possibility (infinity of human imagination and experience) vs. necessity (limitations and contingency of the human body)

At first, schizophrenia seems like to extreme a thing to be placing “just so” as the polar opposite of depression. Helpfully Becker (and Kierkegaard, apparently) acknowledge that there are degrees of this orientation. There are functional schizoid types, like the fictional Walter Mitty, who live in a world of ideas and possibilities but can reckon with their bodily limitation when they need to.

Summary

It’s important to note that this is a different spectrum from the first: this is not about types of beyonds, but just about the orientations people have to their beyonds, once exposed. However, at the extremes of this spectrum (depressive and schizoid), people are driven to change their beyonds. The depressive shuts in; the schizoid runs out.

I thought this polar framing of the phenomenology of depression and schizophrenia was extremely elegant. A lot of things fell into place the more I thought about it. The schizophrenic feels things that their body is not actually experiencing (hallucination); the depressed feels the limits and discomforts of their body all-too-clearly, and is hung up on them. Women are more likely to develop depression. Men experience schizophrenia more severely. Some people who start lifting weights (denying the body its “necessary” comfort and safety in pursuit of a goal that many say is meaningful) find that their depression goes away.

Kierkegaard’s answer

If Kierkegaard ventured into the same fraught territory that Becker does, what was his solution? K wrote about a “school of anxiety,” a kind of process people should go through wherein they remove their helpful repressions and simply face the terror underneath. “The flood of anxiety is not the end for man. It is, rather, a “school” that provides man with the ultimate education, the final maturity.” “The curriculum in the “school” of anxiety is the unlearning of repression, of everything that the child taught himself to deny so that he could move about with a minimal animal equanimity.”

Becker doesn’t really take this view. He believes there is real danger to removed helpful repressions – not an enriching kind of stress. Perhaps the difference is that Kierkegaard believes in God as an ultimate solution to that danger:

A man denies his creatureliness by imagining that he has secure power, “and this secure power has been tapped by unconsciously leaning on the persons and things of his society.” When he admits his creatureliness, he looks for a corresponding Creator, an ultimate cause.

- This is K’s ultimate message, that one learns to seek this Ultimate Power and link himself to it, and to abandon all his dependent links to social/cultural powers. “One goes through it all to arrive at faith, the faith that one’s very creatureliness has some meaning to a Creator”

- And that this leads to true freedom: “Man breaks through the bounds of merely cultural heroism…and by doing so he opens himself up to infinity, to the possibility of cosmic heroism, to the very service of God.”

Chapters 8, 9, and 10 – Otto Rank and the closure of psychoanalysis on Kierkegaard, The present outcome of psychoanalysis, and A general view of mental illness

These chapters have a lot in common so I’m going to combine them. They are about neuroses (mental illnesses) and how they relate to the above ideas.

Is this part actually true?

One would be inclined toward more skepticism when reading this section. Modern psychology has a lot to say about various mental illnesses, and none of it is about “beyonds” or “morbid terror.” I don’t think there need be any incompatibility though. At worst, Becker has used some eerie coincidences to justify forcing some diagnoses into a framework where they don’t belong. But I will say, Becker never strikes me as the kind of armchair psychologist who thinks all medication is bunk and everything can be solved with ideas. A lot of the below, which sounds like proposed causes of neuroses, are more usefully understood as insightful descriptions of neuroses. For example I don’t think Becker aims to say what causes depression (The beyond is too tight? Well what caused that?) as much as to give a more complete description of what depression is, experientially.

Universality of neurosis:

Here Becker takes more shots at the “normal” person, the “immediate man,” diagnosing him, too, as neurotic: “This is neurosis in a nutshell: the miscarriage of clumsy lies about reality. But we can also see at once that there is no line between normal and neurotic, as we all lie and are all bound in some ways by the lies… We call a man “neurotic” when his lie begins to show damaging effects on him or on people around him… Otherwise, we call the refusal of reality “normal” because it doesn’t occasion any visible problems.”

- This is a somewhat popular idea now; the message of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon comes to mind. People sometimes say, “With the current state of the world, you’d have to be crazy to be okay with everything.” Except that when people say this they’re usually referring to politics or climate change or capitalism, but Becker says no, it’s the entire human condition that forces you to adopt these clumsy lies and discrepancies, just to function day-to-day.

Partializing neurosis (depressive):

Becker says a bit more about why the depressive person shrinks further into their restrictive beyond. The person experiences two kinds of guilt:

- First, because they are so hopelessly dependent on their relationships, it is a kind of slavery, and they feel guilt to themselves over this.

- There is also an instrumental guilt that keeps the situation going: they blame themselves for every problem, because to blame the Other would be to dismantle it and lose its transference power. For example, to say that your friend is being callous or neglectful is to admit that they can’t save you. Repressing this, you instead “admit” that in fact you’ve just been a bad friend. And that prevents you from seeking new friends, and so on. From Adler: “Depression is systematic self-restriction that compounds.”

Holistic neurosis (schizoid):

Here, similarly, Becker sheds a modern psychoanalytical light on schizophrenia.

When the person cannot partialize the world and becomes bound up in the chaotic wholeness of life, he feels isolated from the “regular” world, and he lacks the cultural programming that makes life simple. He won’t “pay the price” of nature – he won’t come down to earth and engage with his animal body. He is all about ideas and symbols, leaving the body behind.

- “At its extreme, this describes the schizoid type par excellence. Classically this state was called the “narcissistic neurosis” or psychosis.””

- This is adjacent to the creative type. He avoids clinical neurosis because he actually does take in and engage with the world, but he reworks and recreates it as his own. He is obsessed with his own ideation, but he finds a way to apply it back to his reality.

- “The more totally one takes in the world as a problem, the more inferior or “bad” one is going to feel inside oneself…But it is obvious that the only way to work on perfection is in the form of an objective work that is fully under your control and is perfectible in some real ways.”

- “you objectify that imperfection in a work, on which you then unleash your creative powers. In this sense, some kind of objective creativity is the only answer man has to the problem of life…He takes in the [whole] world, makes a total problem out of it, and then gives out a fashioned, human answer to that problem.””

- “There is no doubt that creative work is itself done under a compulsion often indistinguishable from obsession. In this sense, what we call a creative gift is merely the social license to be obsessed.”

Neurosis as historical

Here Becker points out the historical context of his work. We find ourselves in a time where we no longer share a convincing hero ideology (as cultures did historically, until the Enlightenment).

-

- Becker points to social unrest as a result: “It begins to look as if the modern man cannot find his heroism in everyday life any more… raising children, working, and worshipping. He needs revolutions and wars and “continuing” revolutions to last when the revolutions and wars end.”

Psychology has replaced religion in explaining “the great miracles of language, thought, and morality”.

-

- but even when the human mind is studied scientifically, it leaves untouched the notion of the “soul” or consciousness.

- Psych has danced around the real issue: “Psychology narrows the cause for personal unhappiness down to the person himself, and then he is stuck with himself. But we know that the universal and general cause or personal badness, guild, and inferiority is the natural world and the person’s relationship to is as a symbolic animal who must find a secure place in it.”

- “Modern man is condemned to seek the meaning of his life in psychological introspection, and so his new confessor has to be the supreme authority on introspection, the psychoanalyst. As this is so, the patient’s “beyond” is limited to the analytic couch and the world-view imparted there.”

Perversions

This is Becker’s weakest section in my view. He attempts to explain all manner of sexual phenomena in the context of his grand theory: fetishes, the hermaphroditic urge, sado-masochism, non-hetero orientations. Some of it may come off as delegitimizing to certain groups, but then I remember how much he tore apart heterosexual relationships in earlier chapters. Still, I think he is mistaken here.

The general point is that most “perversions” arise because we need to make sex different in some way in order to feel above our animal nature. This sounds a little too just-so to me, like it could explain anything. And proposing it to explain homosexuality feels pretty far beyond the pale.

It’s difficult, though, because some of it still sounds right, like that basic fetish objects allow us to use the language of cultural symbols (straight hair, high heels, etc.) to “elevate” the sex act with culturally-sanctioned meanings. Aside: I’m a fan of The Last Psychiatrist and I believe he’s made very similar claims.

Overall I don’t very well know what to do with this section.

The Romantic solution

This section goes further into the potential problems of romantic transference. In essence, it’s that your romantic partner is arbitrary, they’re not divine, they might be wrong, so if you feel like a hero in their eyes, that’s not really enough in the grand scheme.

Becker accuses the post-religion modern man of trying to make up in romance what he lost in spirituality (and notice again this additive dynamic where one beyond is pursued as another gets destroyed): “Modem man’s dependency on the love partner, then, is a result of the loss of spiritual ideologies, just as is his dependency on his parents or on his psychotherapist. He needs somebody, some “individual ideology of justification” to replace the declining “collective ideologies.”” And a single person cannot grant so much meaning: “[You] try to make it the sole judge of good and bad in yourself…you become simply the reflex of another person…No wonder that dependency, whether of the god or the slave in the relationship, carries with it so much underlying resentment.”

As a result of this tension, “We often attack loved ones and try to bring them down to size…We see that our gods have clay feet, and so we must hack away at them in order to save ourselves…the deflation of the over-invested partner, parent, or friend is a creative act that is necessary to correct the lie that we have been living, to reaffirm our own inner freedom of growth that transcends the particular object and is not bound to it. But not everybody can do this because many of us need the lie in order to live.”

Then Becker gets into the sexual aspect, which is very enlightening. Becker believes that our taboos and rules around sex came about not only for evolutionary reasons, but because sex is a blatant collision with our animal nature which threatens to trigger all the related terrors. Normally I’m skeptical when I see two different explanations for the same thing, but I think this works. Yes, evolution already explains why males would care a lot about female fidelity and why females would police each other’s sexual availability.. but why are we the only species to have sex in private? Why are we the only species to hate the thought of our parents having sex? Why is event talking about sex considered taboo in many situations?

According to Becker, we make such rules to make sex “ours,” to assert that we’re “above” sex. Sex poses the problem of reminding us of our creatureliness: “It reminds hims that he is nothing himself but a link in the chain of being, exchangeable with any other and completely expendable in himself…He doesn’t want to be a mere fornicating animal like any other…With the complex codes for sexual self-denial, man was able to impose the cultural map for personal immortality over the animal body. He brought sexual taboos into being because he needed to triumph over the body, and he sacrificed the pleasures of the body to the highest pleasure of all: self-perpetuation as a spiritual being through all eternity.”

The Creative solution

This is an entirely new concept that boils down to: creativity works very well as a coping mechanism for the fear of death. That’s because the creator doesn’t lie to themselves about what is meaningful; they resist settling into the familiar beyonds of their culture.

- “Existence becomes a problem that needs an ideal answer; but when you no longer accept the collective solution to the problem of existence, then you must fashion your own…The creative person becomes, then, in art, literature, and religion the mediator of natural terror and the indicator of a new way to triumph over it. He reveals the darkness and dread of the human condition and fabricates a new symbolic transcendence over it.”

This section was pretty esoteric and I’m not sure I fully got it. I’m a creative person (digital art and some other stuff) and I think what he’s getting at is: Creativity allows (or requires!) you to see the world as it is, with all the overwhelming chaos and possibilities, and man’s fragile place in it, because you’ll find meaning in taking all that raw material and making something beautiful out of it. But “beautiful to whom?” is a question with a surprising answer:

- “You wonder where to get authority for introducing new meanings into the world.” And so the artist feels guilt for his grab at immortality. “What right do you have to play God?” The artist, if sober-minded, still knows he’s a creature, which would make his creation meaningless, too. He cannot play God. And he can’t merely create for society, because, as with the romantic partner, they too are arbitrary and cannot really grant meaning.

- “The artist’s gift is always to creation itself, to the ultimate meaning of life, to God.” Freud rejected religion, “But this was precisely Freud’s bind; as an agnostic he had no one to offer his gift to—no one, that is, who had any more security of immortality than he did himself.” But Freud’s student Otto Rank was more approving of religion: “Here Rank joins Kierkegaard in the belief that one should not stop and circumscribe his life with beyonds that are near at hand, or a bit further out, or created by oneself. One should reach for the highest beyond of religion…Rank made complete closure of psychoanalysis on Kierkegaard, but he did not do it out of weakness or wishfulness. He did it out of the logic of the historical-psychoanalytic understanding of man.”

A bit to unpack here: Rank championed this “Creative solution” to the meaning crisis, but he admitted that the creation would have to be on behalf of God, otherwise it’s just crowd-pleasing trivia. This is why Becker says that psychoanalysis “closes” on theology, which would’ve sounded insane to me in any other context.

As a creative atheist, I don’t know where that leaves me. I do find creation meaningful, and I do find myself absorbing more of the world than most can accept (I judge this by how often people say to me, “that’s so depressing, I could never believe that!” about things that seem perfectly acceptable to me). But it’s true that I create for my society, and I do recognize that, on paper, that doesn’t really add up to any meaning. One lasting notion this book left me with was, “If I ever lose my creative energy, or lose the motivation to show beauty to my peers, I’m going to be in real trouble.”

More on Christianity

Here are some more reflections, from throughout the book, on how Christianity answer the problem of death.

“When man lived securely under the canopy of the Judeo-Christian world picture he was part of a great whole; to put it in our terms, his cosmic heroism was completely mapped out, it was unmistakable…Christianity took creature consciousness—the thing man most wanted to deny—and made it the very condition for his cosmic heroism.”

- I was raised Christian and this is all pretty undeniable. It doesn’t really help if you don’t believe it’s true, but there are some powerful ideas here, and I think their unique ability to alleviate fear of death is partly responsible for Christianity’s memetic success. It says yes, you are an animal, and just an animal; there is no little deity inside you hopelessly struggling to get out. But there is a power outside, and this power does adequately stand in for the entire universe, so you will transcend all your physical limitations by living rightly with it. And the way to live rightly with it is to acknowledge your nature (as a creature). And even if you fail that, you will not be annihilated.

- I should mention though that Christianity, like any religion, can also just become a set of rules, making it another relatively restrictive beyond. It’s interesting to look at people who belong to the same religion but have different psychological profiles, and see how their personal theologies reflect the size of beyond they require. There are versions of Christianity that run the whole gamut.

Chapter 11 – What is the heroic individual?

In this chapter Becker asks (as many readers have likely asked), “Ok, which heroism is preferable then?”

“The most one can achieve is a certain relaxedness, an openness to experience that makes him less of a driven burden on others.” Indeed, some beyonds give us enough freedom to actually make the world better for others, while other beyonds mainly impose costs on the people who have to protect us. So I think the argument is, all else being equal, at least help others if you can.

- One silver lining: at least we get to experience more than dumb animals: “When evolution gave man a self, an inner symbolic world of experience, it split him in two, gave him an added burden. But this burden seems to be the price that had to be paid in order for organisms to attain more life”

- Of course, we can still conceive of a world where we’d get such a life without paying that price, and that wish torments us. I told you at the beginning there wasn’t a satisfying solution.

Also in this chapter, a bitter pill for anti-aging optimists: from Jacques Choron: “Postponement of death is not a solution… there still will remain the fear of dying prematurely.” And a premature death would deprive man “not of 90 years but of 900.”

Limits of psychotherapy

Becker’s dark perspective allows him to work out what appear to be some damning truths about the field of psychology. Becker rejects what he calls the narrative of “unrepression” – the idea that we can achieve the best versions of ourselves by facing reality more and more directly. Unrepression will not save us, he says, for reasons we’ve already seen. We need illusions and transference objects, or we are utterly overwhelmed or petrified. And so, the lofty claims of the “whole therapeutic enterprise” can be called into doubt. Why should a patient seek to uncover the ways they deceive themselves, if all that awaits is either terror or further self-deception?

- Becker outlines: In America, the Christian myth was replaced by the Hollywood myth (thanks to commercial industrialism), and now that myth is being replaced by a paradise-through-self-knowledge myth. Psychotherapy is the new means by which people seek rightness with the universe. And so we get patient-doctor transference: patients believe their doctors not because of the ideas themselves, but because of the role the doctor is playing – must play. In this way, psychotherapy is less about fixing one’s neuroses (which can’t be entirely fixed), and more about paying someone to symbolically take responsibility for setting us on a good path.

- Similarly, in an earlier chapter, Becker takes some shots at Maslow’s concept of “full humanness,” that nirvana supposedly waiting at the top of the hierarchy of needs. Becker doesn’t expect much of a victory there: “Full humanness means full fear and trembling…Maslow was too broad-minded and sober to imagine that being-cognition did not have an underside; but he didn’t go far enough toward pointing out what a dangerous underside it was—that it could undermine one’s whole position in the world.”

Have you ever found it odd that all the advice about “comfort zones” says to step beyond them? Is that a universal solution that most people just don’t follow for some reason? Are there no people who desperately need to hear the reverse and stay inside their comfort zones? There are, says Becker, and this fight for constant expansion is shortsighted. It doesn’t account for the dangers people face. The “step out of comfort zone always!” people don’t have to answer to those who wind up crazy, broke, or dead. The comfort zone is there for a reason. It’s “lindy,” as they say on Twitter. That doesn’t mean there aren’t overestimates of risk—there are bound to be plenty when our risk-meters aren’t evolved for the modern world. But the idea that expanding one’s comfort zone is always good is reckless, and it doesn’t take much thought-experimenting to see that.

Summary

A good quote to wrap up the thesis: “The orientation of men has to be always beyond their bodies, has to be grounded in healthy repressions, and toward explicit immortality-ideologies, myths of heroic transcendence.

Old ideas, recontextualized

I said that Becker’s thesis was an excellent coordinate system. The following are some ideas I personally held before reading, that I feel are more elegantly represented in Becker’s terms. The original ideas are first-level bullet points, recontextualizations are the second-level bullet points:

- Substance vs symbols – symbols don’t always correspond to the real thing; you should root your identity/actions in substance instead.

- This book made me realize that the push to discard symbols in favor of substance, is the very same push for unrepression that Becker warns about. It’s the dangerously optimistic view that everyone is better off shedding all their cultural symbols. In truth we need the symbols to function at all.

- That being said, the creative type does not speak with cultural symbols, but fashions his own symbols, and he must occasionally engage with the substance more directly in order to do this.

- We’re happiest at the border of order and chaos (from Jordan Peterson, and the general “comfort zone” rhetoric of many self-help people).

- We settle into a beyond that satisfies our twin ontological motives in exactly the amounts we need: we have safety, and we have adventurous work ahead.

- Bridge to Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: His message was: People exist as either True Believers or Individualists, and this is the real political spectrum we should pay attention to. If you’re familiar with that book, the following will make sense.

- The TB has a specific transference object due to a specific set of circumstances. Instead of aiming lower after consistent failures (and shrinking into tighter beyonds), they abandon any hope of self-heroism and give the self up in favor of identifying with a movement.

- TB is ontological feminine in the extreme, in the sense that he is entirely embedded; his experiences are entirely mediated by an Other.

- The Fanatic, who tends to lead True Believers, is a type of self-created man. S-C man is aware of his impotence (perhaps through failed creativity) and will act drastically to defy the world in which such impotence exists. He can do this by starting a mass movement: he either invents dogmas or clings to existing ones. He’s more daring (or more filled with rage) than an ordinary True Believer.

- The Individualist is everyone who occupies a beyond that still prizes some form of individual heroism.

- Bridge to TheLastPsychiatrist/Nietzsche: People buy into cultural-symbolic markers of identity instead of caring about what they actually do with their lives. They go to great lengths to avoid self-discovery and change.

- Because self-discovery warrants change, and change requires you to step into chaos. Instead, we choose to avoid a challenging life, and we find easy transference objects – human authorities, organizations, video games.

- TLP’s narcissist is completely covered in DoD. And TLP’s positive prescriptions tend to be vague because he must avoid the same dead-end that DoD runs into. In this way, TLP is more optimistic, making it seem (at first) like you can make a few corrections, dispel a few illusions, and you’ll be “right” again.

- “The best use of freedom is to choose how you’re going to restrict it”

- We choose our beyonds. They restrict not only our actions, but our ambitions and the ways we interpret our experiences.

- The “hierarchy of urges” / Human complete problems—Natural urges put us into finite games, but the task of arranging our urges for the optimal experience is a uniquely human task and amounts to infinite games.

- The ability to reorder and channel the natural urges makes us able to function in one hero project or another. We direct ourselves in the given patterns, and the resulting cultural/symbolic “success” tells us we’ve mastered our mortality.

- To live happily (or at least without despair) is an infinite game. It requires that one find a suitable hero project, but because the project can expire or you can fail at it, you must sometimes find a new one.

Pingback: False Generalists - True Generalist