I think about ads a lot. That may be because I work in consumer technology, the medium through which most advertisements are delivered nowadays. Or it may be because I have strong feelings about consumerism, which is really the spirit in which every ad is made. Or, it may be that since I’ve started trying to shut ads out of my life, I’ve become more aware of the few that manage to slip through.

In this series of posts, I’ll write about the subtle costs of seeing ads, why targeted ads are worse (not better, as some consumers think), and what “good ads” might look like in a modern, digital, attention-thirsty world. I’m certainly not the first person to complain about ads, but I believe I have a few new ideas to throw on the pile. Or, at least, I hope I can articulate a well-known problem in a new way.

Part 1: Ads are costly

I believe the long-term effect of virtually all ads on consumers is a drop in well-being, and we should take a more aggressive approach to avoiding them. Most estimates say we see a few thousand ads every day, and it’s easy to see that that number is growing. As technology continues to grow more popular and more personal, ads are finding their ways into more of the blank spaces in our lives. More of our tasks and errands are now done over the internet, through apps and websites eager to make money, on screens that can easily accommodate an ad here or there. Our fora, the places where we meet, socialize, and express ideas, have been migrated from real-life spaces (street-corners, parks, bars) to virtual worlds created and owned by private companies (Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, YouTube). As this trend continues, we’ll only feel the following adverse effects more strongly.

Financial waste (the boring one)

Let me quickly mention the oldest and most basic complaint about ads: that they lead you to buy things you don’t need or even want very much. Lots of people are concerned about this, but lots of others aren’t: they claim that ads don’t “work” on them. “If I don’t want the product, why would 30 seconds of fake enthusiasm and cheesy humor change my mind?”

I don’t personally think this way anymore. I accept the argument that ads put ideas and associations in the back of our minds, in our subconsciouses, and then those ideas get called up later, “randomly,” when we need to make quick decisions. That’s why we rarely have trouble picking one brand out of the several on the shelf or thousands online. And most of us, if we came into an extra $200 for whatever reason, would have no trouble deciding what (or whose) product to spend it on. Thanks to ads, brands get associated with good feelings (familiarity, humor, ethics, etc.), and products get associated with aspirational lifestyles (“intellectual,” “ambitious,” “carefree,” etc.). And suddenly, without doing any conscious calculation, we “know” which brands to endorse and which products to buy. Inevitably, this process will lead us to make purchases that aren’t as economically rational as they could be.

No, the reason that ads don’t work on me is that I don’t see them in the first place. But we’ll get to that in the next post.

Beyond financial waste

There is more to consider than just the issue of buying what you don’t need. Let’s assume that when you see ads, you’re very good at both 1) not buying the products, and 2) rejecting the associations they’re trying to make. I’d like to argue that saying no to ads still has a cost. And I’m not talking about ego depletion—the idea that you lose willpower throughout the day as you exert self-control, making it more and more likely that you’ll slip up or burn out. Apparently, this is not a reliable theory of willpower anymore (thanks for wasting our time, modern psychology). No, apart from that, saying no still has a cost.

Attention waste (the interesting one)

If we look beyond the potential waste of money, we find that there’s also a certain, not potential, waste of attention. Whether we say yes or no to something, there is an attention cost to even considering the decision. And unlike money, we cannot get our attention refunded to us if we’re unhappy with how we spent it. Money can be spent, refunded, and spent again, but a moment of your attention is just that, a moment in time. It’s irreversible. So hopefully our attention isn’t split between too many things at once, and hopefully it’s spent on something we find worthwhile.

But when something is not worthwhile and wastes our finite attention, we don’t always express this in the most accurate way. Often, especially with ads, we use the term “annoying” or some synonym. When we call something annoying, we are assigning a property to that thing (I mean a property as it’s understood in Western philosophy, as a characteristic of an object). But most properties simply belong to their objects and don’t necessarily affect other objects. An apple is red, but that doesn’t make you red, or make you only able to see red things.

So when we describe an ad by simply giving it the property “annoying,” this hides the fact that a transaction is taking place: we are paying attention-time (which we cannot take back) to the thing being described. This is like saying, “He’s dishonest,” when what you really mean to say is, “He stole my watch.” It’s an unfortunate quirk of language; let’s overcome it by being aware of the fact that “annoying” things are things that actually take and waste our finite attention-time.

Focus cost

Here’s another thing to note about attention-time: there’s even a cost to switching what we spend it on. When something like an ad grabs our attention, we must take some amount of time to refocus that attention. When you’re working on the computer and you see an ad, there’s the time-attention you spend taking in the ad, but then there’s also the time-attention it takes to return to what you were doing. “What was I thinking about just now?” Consider too that most ads are expressly designed to interrupt your train of thought.

The amount of time it takes us to return to our previous thoughts may seem incredibly small, but multiply it by a few thousand per day, and then multiply that by the number of days in a life. We have to acknowledge that at some point, as ads get more and more ubiquitous, the amount of wasted attention could seriously hurt our ability to enjoy our lives.

Ego cost

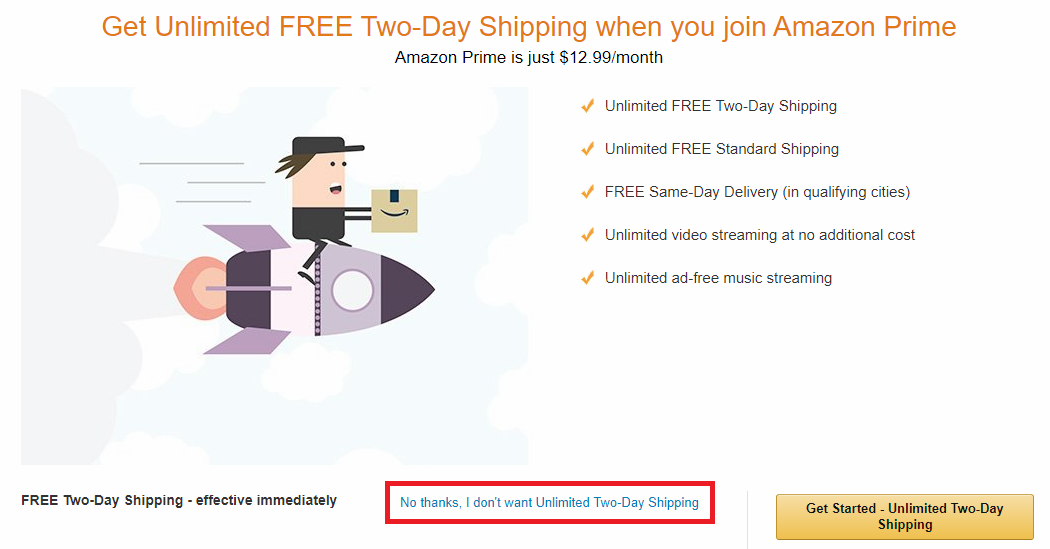

Here’s another cost of saying no, and it’s totally unrelated to the above. Have you noticed the way some ads try to shame you out of clicking away? Look at this ad for Amazon Prime, which often shows up midway through the checkout process.

“No thanks, I don’t want Unlimited Two-Day Shipping.” Yep, that’s me. I’m just a lame person who doesn’t want cool-sounding (unnecessarily capitalized) things in my life.

After some quick searching I learned that there’s already a term for this (and a Tumblr account to collect examples): “confirmshaming.” It’s not the term I’d choose, but Tumblr got there first.

- “No thanks, I’d rather not keep up-to-date”

- “No thanks, I’m not into savings”

- “No thanks, I like paying full price”

And sure, we know these statements aren’t true. We know their descriptions of us are disingenuous. But isn’t it still somewhat uncomfortable to physically check a box saying “I don’t want [obviously good thing]” or “I’m not [obviously good trait]”? That discomfort is the ego reacting to a threat. The ego doesn’t act on what it knows; it reacts to what it hears. It is concerned precisely with our status and how we are being perceived/talked about. That’s why a large number of grown, civilized men will still jump up and prepare to fight (or at least seriously consider it) if someone simply calls them the wrong word: the ego won’t allow it to be said. That’s also why a verbal proclamation of one’s own wrongdoing or weakness is such a profound thing; it’s the complete rejection of the ego (and all the status that it so desperately tries to protect).

Confirmshaming is the advertiser’s attempt to hold the ego hostage. They say something unfavorable about us, ask us to assent to it, and then we can either change our mind or experience the discomfort of killing our ego in that moment. Ego cost is even harder to measure than attention-time cost, but let’s at least acknowledge that it’s there, we experience it, and ads are inflicting it on us when we try to say no.

Conclusion

What I’ve tried to show here is that ads are costly to consume—costly enough to be alarming when we consider how many of them we see on a daily basis. But we didn’t even get to the fun part yet. In the next post, I’m going to dig into the hot-button subtopic of this hot-button topic: targeted ads.