In the last post, I concluded that the question “Why ___?” is the request for a reason for something to be the case, and that the answers to this question either state a cause or state the desired effect of the thing being asked about (which actually just implies that the cause is some acting agent with a desire or motive toward a certain effect). But, we find that most “Why ___?” questions have more than just two correct answers, even if the answers can only take, at most, these two forms. In this post I want to explore why many different answers can be given to the questions of “Why ___?” and why some answers seem better than others, even if they are all technically correct.

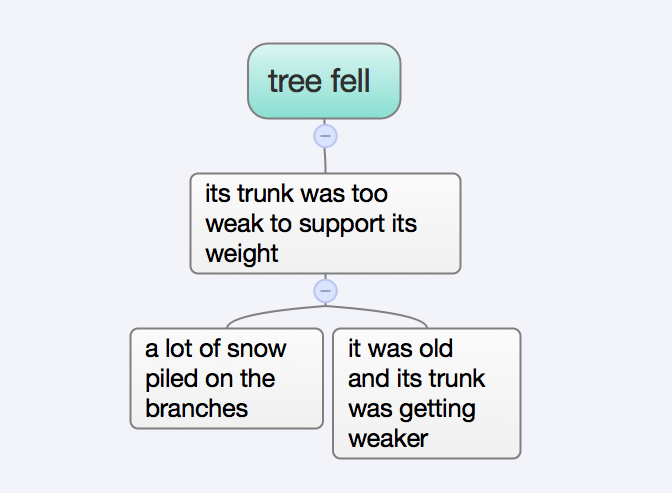

An example question I gave in my last post was, “Why did the tree fall?” and the answer I made up was, “Because its trunk was too weak to support its weight.” What other answers could I have given? “Because a lot of snow piled up on the branches.” “Because it was old and its trunk was getting weaker.” All of these answers could be true in the same instance, and they all seem to answer the question by giving a cause for the tree to be falling. What is the relationship between these different —but correct— causes? After thinking about it further I feel confident in the claim that they are naturally connected in a tree structure (seriously no pun intended) where every “root” is a cause for something above it, and each cause branches down into its own composite “root” causes below it.

As we can see, the two bottom causes are linked to the middle node, not directly to the top node. This is because they did not cause the top node event (tree fell) directly, but necessarily caused the middle event (the trunk was too weak to support its weight) first. Of course this chart isn’t complete. The two causes at the bottom could each have their own causes, and so on:

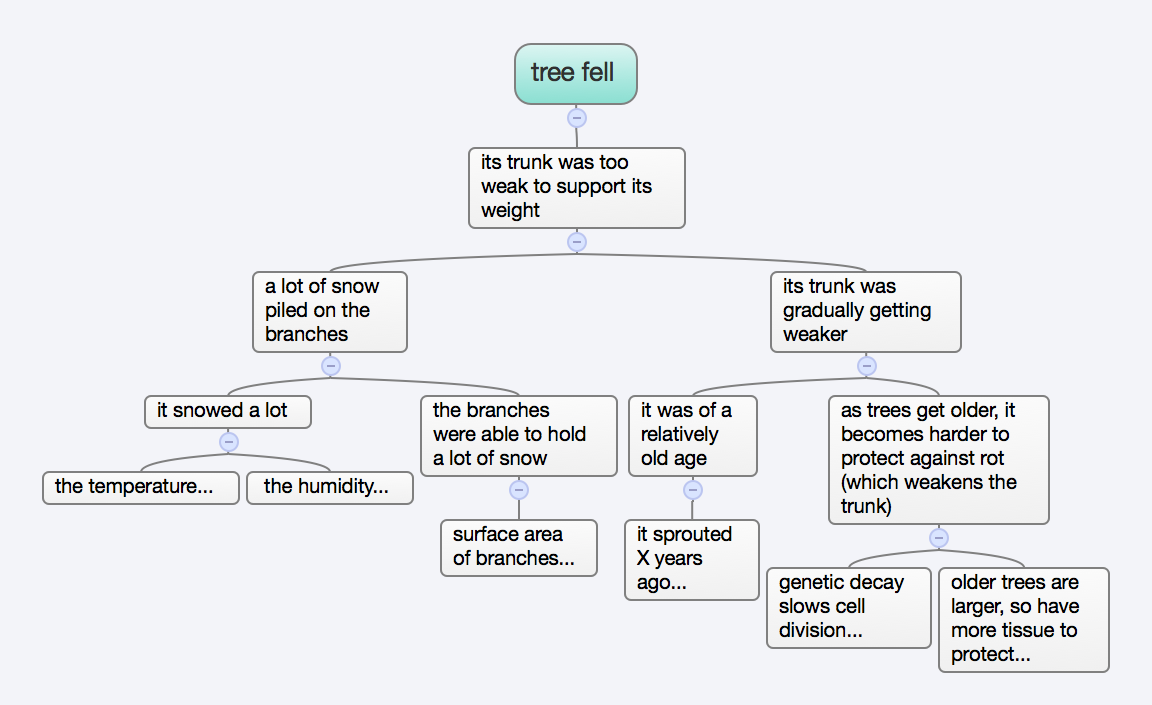

I put “…” where I didn’t know enough to go any deeper (and I had to do some quick research to be able to write even this much). And still, I’m sure I left out important steps in between these middle levels as well. If I did know more about biology and ecology and weather etc., I could keep writing causes and splitting them into further causes. But, you’ll notice that while the top three nodes on the chart seem like good answers, the statements farther down relate less directly to the original question. The statements higher up on the tree are the more direct causes of the event at the very top. And the highest causal node, directly under the event itself, is what I’ll call the singular cause.

The singular cause alone guarantees a certain effect. To use the previous example, the sky is blue because the particles of our atmosphere reflect more blue light than other colors of light — a material that reflects more blue light than other colors must appear blue.

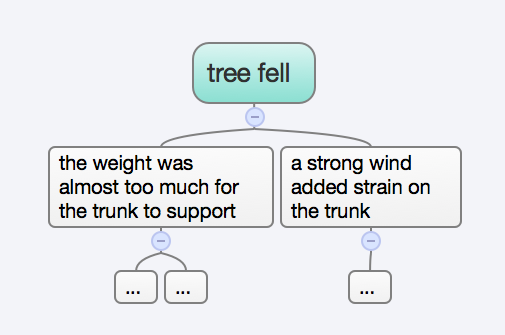

It seems to me that it’s usually very hard to state the singular cause concisely. Even the one in the example above is unlikely to be true in real life. Trees don’t really fall down from just their weight; they fall when they weigh almost too much and then a strong wind or other force comes along. We can amend our chart to include this detail, but then we appear to have two “singular causes” that together result in the event:

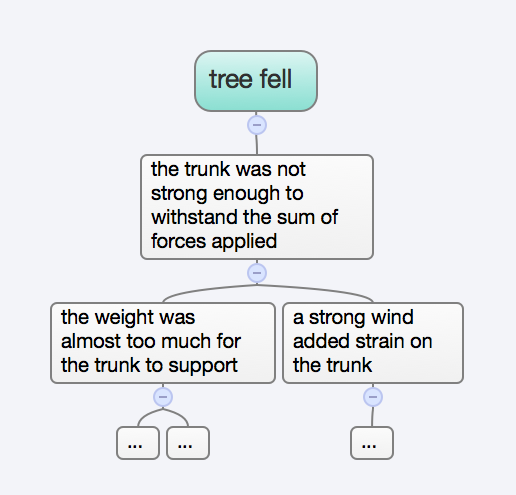

In my imaginary scenario, these two causes both had to be present for the event to have occurred—but life was simpler when we could map a single cause to the final event. We can return to this simplicity by writing a new statement that encompasses both of these “singular causes” as its own component causes and is itself a singular cause of the final event:

So far, this new singular cause is the most complete answer we’ve found for the original question, but it is not the most helpful. It states the result of all the other causes beneath it, and so it itself must be very vague, lacking detail. It is such a generalized statement that it can really be thought of as the definition of the final event. What does it mean for something to fall, if not that the sum of the forces applied to it was greater than the sum of forces holding it upright? And for the other example: what does it mean for something to “be blue,” except that it reflects more blue light than other colors? The singular cause, which is the result of all the other causes in the tree, is both the cause and definition of the final event.

This makes it a terrible answer to the question “Why ___?” The asker already knows, in some deep conceptual way if not explicitly, that the trunk was not stronger than the sum of forces applied. In fact, if we look back at those other causes in the tree, we’d guess that there are probably several that the asker has already assumed.

So, if the singular cause at the top of the tree is not a helpful answer, and the causes at the bottom just branch off into increasing complexity, how does one best answer “Why did that tree fall?” You may have guessed already: there is no best answer. The answerer will choose to name a cause that falls somewhere in the tree—any one that gives “enough” detail and that the asker isn’t likely to know already. There are likely many causes in the tree that would qualify as acceptable answers.

The same goes for the prescriptive case (defined in Part 1). If we are asking, for instance, “Why did you do ___?,” then the singular cause at the top of the tree would be something along the lines of “Because I desired the effect that I expected ___ to bring, and I had the ability to do ___.” This doesn’t reveal anything useful and is essentially the definition of making a decision and acting on it.

“Why ___?” is a messy question. My hope is that, by being aware of the arbitrary nature of the answers that it invites, I can be more efficient as both the asker and answerer. As the asker, I can better articulate why an answer I received, although correct, is not satisfying to me. As an answerer, I can be more conscious of my own process of choosing the “best” cause that provides the most relevant details that the asker is missing (or, for the devious and manipulative among you, the answer that avoids the details you want to avoid or draws attention to the issues you want to focus on).

Pingback: Why and Why Not (Part 1) - Patrick D. FarleyPatrick D. Farley